Learning Arabic allows Muslims to understand the Quran directly, access 1,400 years of Islamic scholarship, and experience worship with full spiritual presence rather than memorized sounds.

For many Muslims, Arabic is limited to prayer and Quranic recitation. We learn pronunciation for Salah but often miss the meaning.

Umar ibn al-Khattab, the second Caliph, said, “Learn Arabic, for it is part of your religion,” highlighting the link between language and faith.

Learning Arabic is a vital spiritual, intellectual, and personal investment. It offers direct access to divine revelation, forms the basis of Islamic law, deepens daily prayers, and connects one to a rich global Islamic heritage.

Why Did Allah Choose Arabic for the Quran?

Allah chose Arabic for the final revelation because of its unmatched precision, vast vocabulary, and ability to convey multiple layers of spiritual meaning in concise speech.

The Quran repeatedly calls itself an “Arabic Quran,” as in Surah Yusuf (12:2), linking its clarity and intellectual depth directly to the Arabic language.

Scholars like Ibn Kathir argue that its revelation in Arabic was necessary because it is the noblest, most comprehensive language, possessing jawami’ al-kalim (comprehensive speech). This linguistic choice was deliberate, aligning the final divine message with the most sophisticated human language.

What Is the Linguistic Miracle of the Quran?

The Quran’s linguistic miracle (I’jaz) is its inimitable combination of rhetorical devices, syntactic structures, and rhythmic cadences that no human can replicate despite 1,400 years of attempts.

The phonetic qualities matter profoundly. The rhythm, rhyme, and specific sounds of Arabic letters are designed to penetrate the heart.

Listening to a beautiful recitation can bring tears even without full comprehension, but when understanding combines with sound, the experience becomes transcendent.Pre-Islamic Arabs, masters of linguistic excellence, were silenced by the Quran’s revelation.

The Quran issued a challenge (tahaddi) in Surah Al-Baqarah (2:23) to produce a single comparable chapter. After 1,400 years, this challenge remains unmet. Because this miracle is linguistic, the Quran’s divine essence is inseparable from its Arabic form.

Its sonic resonance, depth, and density cannot be replicated in translation; therefore, translations are merely interpretations of its meanings. The phonetic qualities,rhythm, rhyme, and specific sounds,are crucial, penetrating the heart and creating a transcendent experience when combined with comprehension.

| Quranic Verse | Key Message | Significance for Arabic |

| Surah Yusuf (12:2) | “An Arabic Quran so that you may understand” | Links the language directly to human comprehension |

| Surah Az-Zumar (39:28) | “An Arabic Quran, without any crookedness” | Asserts linguistic perfection as moral guidance |

| Surah Ash-Shu’ara (26:192-195) | “In the plain Arabic language” | Emphasizes clarity (mubin) as a vehicle for warning |

| Surah An-Nahl (16:103) | “This is a clear Arabic tongue” | Refutes claims of human origin by contrasting with foreign tongues |

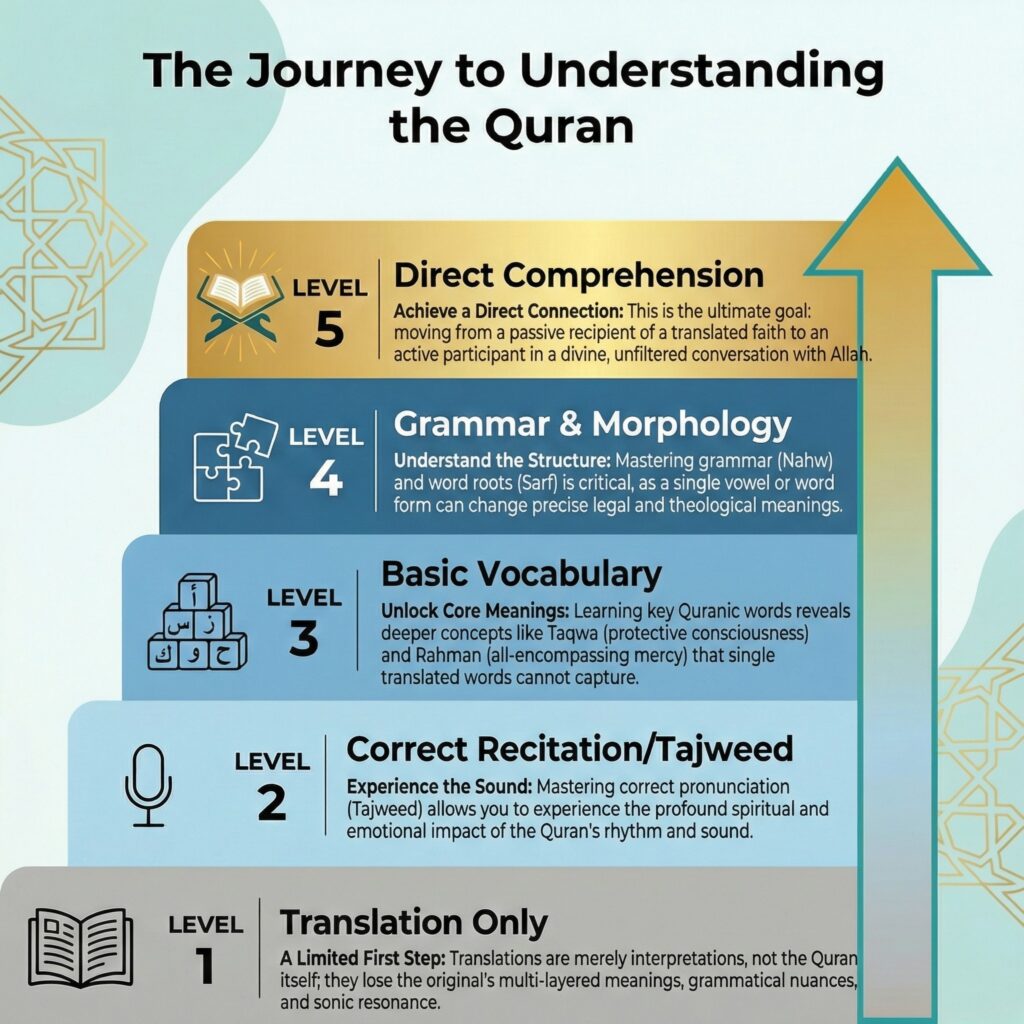

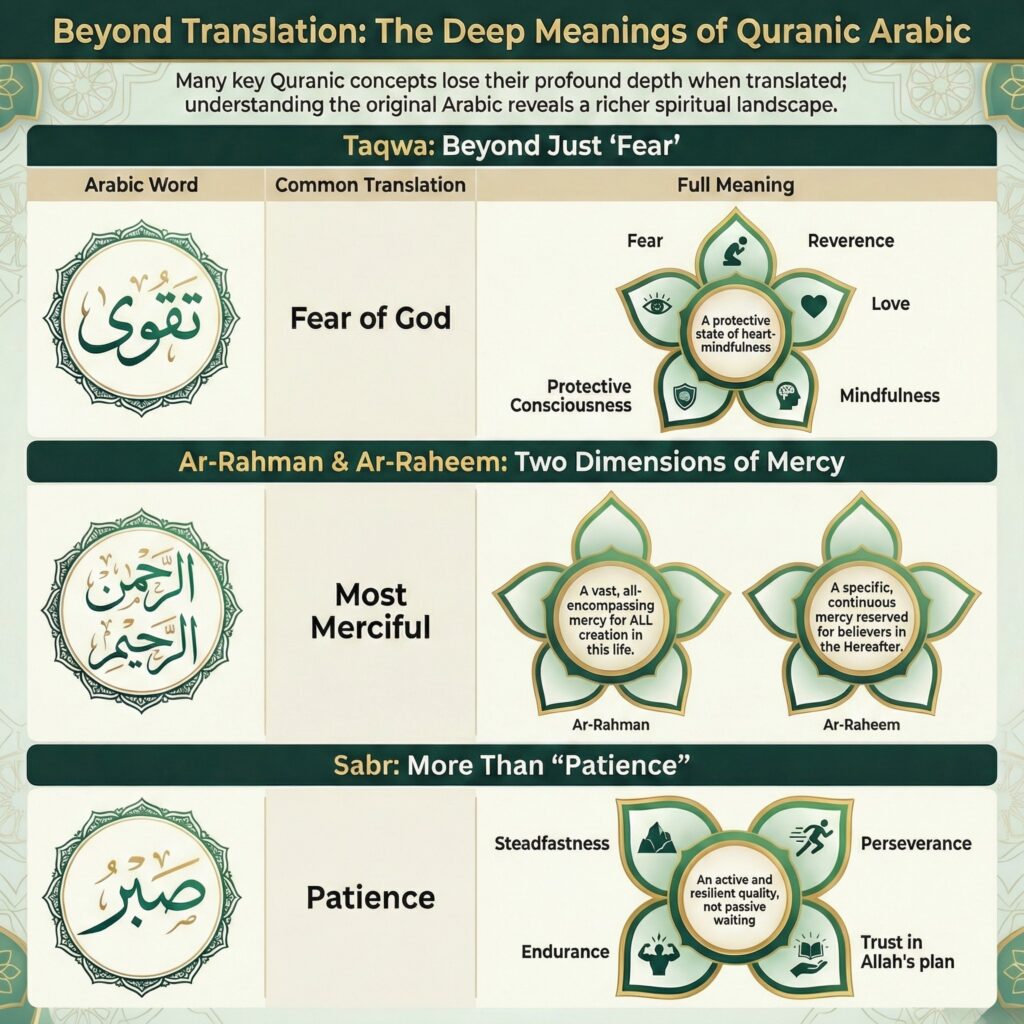

What Gets Lost When Reading Quran Translations?

Translations lose the multi-layered meanings, grammatical nuances, and sonic resonance that make the Quran a linguistic miracle, reducing divine speech to human interpretation.

Arabic is a Semitic language built on a tri-consonantal root system, where thousands of words derive from a single three-letter root. Each word carries not just meaning but morphological information about intensity, duration, and relationship to the root concept. Translation flattens this richness into linear equivalents.

Consider these examples of what disappears in translation:

- Taqwa is commonly translated as “fear of Allah,” but this barely scratches the surface. The word encompasses a protective consciousness of God that guides every action, combining fear, reverence, love, and mindfulness into one powerful concept. It is the state of being so aware of Allah’s presence that you guard yourself from anything that might displease Him.

- Rahman and Raheem both derive from the root R-H-M, signifying mercy. But Rahman refers to a vast, all-encompassing mercy extended to all creation,believers and non-believers, humans and animals, in this life. Raheem refers to a specific, continuous, eternal mercy reserved for believers in the Hereafter. A translation might use “Most Gracious, Most Merciful,” but the subtle distinction between the scope and timing of these mercies is lost.

- Sabr is translated as “patience,” but it is far more active and resilient. Sabr is not passive waiting but steadfastness, perseverance, and endurance in the face of adversity while maintaining trust in Allah’s plan. It is a dynamic quality that requires effort and faith.

When you read the Quran in translation, you are reading someone else’s understanding of these words. When you learn Arabic, you begin to build your own direct relationship with the text, allowing Allah’s words to speak directly to your heart without any intermediary.

Why Is Arabic Necessary for Islamic Scholarship?

Scholars like Imam al-Shafi’i and Ibn Taymiyyah classified Arabic mastery as obligatory for deriving Islamic law, since grammatical errors can fundamentally distort divine rulings.

In Islamic Law (Fiqh), Arabic is the core tool for legal derivation. A Mujtahid (qualified jurist) must master three linguistic sciences, Nahw (Grammar), Sarf (Morphology), and Balaghah (Rhetoric) to avoid errors that distort divine intent.

Imam al-Shafi’i stressed that deep Arabic knowledge is an absolute prerequisite for deriving rulings from the Quran and Sunnah, arguing that one cannot understand divine commands without it.

The grammarian Ibn Jinni stated: “Weakness in the Arabic language leads to weakness in understanding the core teachings of the faith.” Scholars categorize Arabic mastery as an individual obligation (fard ‘ayn) for those seeking to understand their worship, and a collective obligation (fard kifayah) for the jurists responsible for legal rulings, ensuring the community preserves and transmits the faith accurately.

| Linguistic Science | Function in Islamic Law | Example Application |

| Nahw (Grammar) | Determines syntactic relationships and case endings | Vowel markers in the verse of Ibrahim’s test (2:124) clarify God tests Ibrahim, not the reverse |

| Sarf (Morphology) | Analyzes word roots and derived meanings | Deriving different intensities of mercy from the root R-H-M |

| Balaghah (Rhetoric) | Identifies metaphors, emphasis, and linguistic styles | Distinguishing literal commands from metaphorical expressions |

| Mantiq (Logic) | Ensures sound reasoning and consistency | Determining if a command indicates obligation or recommendation |

How Does Arabic Grammar Affect Islamic Law?

A single vowel mark in Arabic can change a legal ruling, as demonstrated in ablution laws where the particle “bi” determines whether part or all of the head must be wiped.

Arabic grammar critically impacts Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), notably in interpreting particles and verb tenses. For example, in the verse on ablution (5:6), the particle “bi” in wamsahu bi-ru’usikum (“wipe over your heads”) determines whether one must wipe a portion of the head or the entire head,a ruling that affects millions of Muslims daily.

Similarly, grammar clarifies theological correctness, as seen in the verse regarding Prophet Ibrahim (2:124), where vowel markers ensure God is the tester, not the tested. Furthermore, the use of the present/future tense (fi’l al-mudari’) in narrations about legal residency (Watan Shar’i) can define what constitutes a permanent residence for calculating a traveler’s prayer.

These grammatical interpretations are not abstract but form the practical foundation for how 1.8 billion Muslims organize their worship and lives.

Why Do Muslims Pray in Arabic?

Muslims pray in Arabic to maintain global unity, preserve the exact words taught by Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, and enable deeper spiritual focus through direct comprehension.

The Adhan (call to prayer) serves as a public declaration of Islam’s core tenets: the greatness of God (Takbir), the oneness of God (Tawhid), and the finality of the Prophetic message. According to the majority of schools of jurisprudence,including the Hanafi, Maliki, and Hanbali schools,it is not permissible to call for prayer in any language other than Arabic.

This requirement ensures that the call to prayer remains a universal symbol of the Ummah. A Muslim can move from a village in Nigeria to a metropolis in Indonesia and immediately recognize the call to worship, fostering a sense of global unity and shared identity. When you hear “Allahu Akbar” echo from a minaret anywhere in the world, you know exactly what is being proclaimed and what it demands of you.

Praying in Arabic also preserves authenticity. The words recited in Salah are the exact words taught by Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, transmitted through an unbroken chain of 1,400 years. This preservation is considered essential for maintaining the integrity of Islamic worship.

| Adhan Phrase | English Meaning | Theological Significance |

| Allahu Akbar | Allah is the Greatest | Affirmation of divine supremacy over all worldly affairs |

| Ash-hadu alla ilaha illa-llah | I bear witness there is no god but Allah | Declaration of strict monotheism (Tawhid) |

| Hayya ‘ala-s-Salah | Hasten to the prayer | Invitation to communal worship and spiritual discipline |

| Hayya ‘ala-l-falah | Hasten to true success | Redefining success as spiritual rather than material |

| As-Salatu khairun min an-naum | Prayer is better than sleep | Recited only at Fajr; prioritizing spirit over comfort |

How Does Learning Arabic Transform Your Worship?

Understanding Arabic transforms Salah from mechanical movements into intimate conversation with Allah, creating the state of Khushu’ (spiritual focus and serenity) that brings unearthly satisfaction.

Learning Arabic transforms a non-native Muslim’s ritualistic performance into true Khushu’ (spiritual focus and humility).

Understanding the words makes prayer an unfiltered conversation with the Divine. For instance, knowing Surah Al-Fatiha‘s depth,that “Alhamdulillah” means all praise belongs to Allah, and “Rabb al-‘Alamin” signifies the Creator/Sustainer with a deep, personal relationship,adds profound weight.

The grammatical emphasis in “Iyyaka na’budu wa iyyaka nasta’in” (You alone we worship and You alone we ask for help) powerfully declares exclusivity to Allah. This deeper understanding makes Salah a transformative source of spiritual energy and refuge, not just an obligation.

Is It Compulsory to Learn Arabic in Islam?

Learning Arabic is not obligatory like prayer or fasting, but scholars strongly recommend it for anyone seeking understanding beyond surface-level faith and protecting themselves from misinterpretation.

For the average Muslim, learning Arabic is not a core religious pillar; reliance on translations is common. However, scholars like Imam al-Shafi’i distinguished its necessity: it is fard ‘ayn (individual duty) for those seeking a deep understanding of worship, and fard kifayah (collective duty) for the scholarly class to preserve and teach the faith.

Beyond mere obligation, Arabic is crucial for intellectual independence, helping believers move past surface-level knowledge and avoid misinformation. With two-thirds of global Muslims lacking Arabic proficiency, this literacy gap creates dependence on potentially biased translations, leading to “faith illiteracy” and vulnerability to distorted Islamic teachings.

What Are the Cognitive Benefits of Learning Arabic?

Learning Arabic enhances working memory, visual-spatial processing, and metacognitive awareness, with Quran memorizers showing significantly higher self-regulation in learning.

Learning Arabic as a second language provides significant cognitive and psychological advantages beyond its religious importance. The unique right-to-left script and connected letters enhance visual-spatial processing and attention allocation compared to simpler Latin scripts.

The discipline of Hifz (Quranic memorization) is a powerful mental exercise that improves working memory and concentration. Studies show memorizers, like Indonesian students, exhibit higher metacognitive awareness,the ability to manage one’s own learning.

For religious learners, the “spiritual-integrative” motivation is a powerful intrinsic driver. This deep desire to connect with divine texts fosters greater persistence, helping learners successfully navigate Arabic’s complex morphology and grammar.

| Cognitive Domain | Benefit of Arabic Study | Research Context |

| Working Memory | Exceptionally strong retention and storage | Linked to success in morphologically rich languages |

| Visual-Spatial Processing | Enhanced right-to-left and connected script processing | Developed through automatic letter recognition in religious practice |

| Metacognitive Awareness | High capacity for self-reflection and learning regulation | Pronounced in students with prior Quranic memorization |

| Analytical Strategies | Stronger pattern recognition and root identification | Facilitates navigation of tri-consonantal root systems |

| Affective Resilience | Use of Islamic coping strategies to manage anxiety | Found in learners using spiritual-integrative motivation |

How Can I Start Learning Arabic Effectively?

Dedicate 20-30 minutes daily to structured study focusing on Quranic vocabulary, basic grammar, and correct pronunciation, using spiritual motivation to sustain long-term commitment.

The journey to Arabic proficiency begins with the right mindset and methodology. Here’s a practical roadmap based on how successful learners have approached the language:

1. Set Your Intention (Niyyah)

Approach learning Arabic not as a tedious academic subject but as an act of worship (ibadah). Your goal is to get closer to Allah by understanding His words. This intention will fuel you when motivation wanes. Remember the Prophet’s ﷺ words: “Actions are but by intentions, and every man shall have only that which he intended.”

2. Build Consistency Over Intensity

Studying for 20-30 minutes every day is infinitely more effective than a 5-hour session once a week. The Prophet ﷺ said, “The most beloved of deeds to Allah are those that are most consistent, even if they are few.” Make Arabic a small, non-negotiable part of your daily routine. Link it to an existing habit, like after your Fajr or Isha prayer.

3. Master the Foundations First

Start with the Arabic alphabet and pronunciation (makharij). Correct pronunciation is essential, as mispronouncing a letter can change a word’s meaning entirely. Learn the rules of Tajweed simultaneously, ensuring you recite the Quran as it should be recited.

4. Focus on Quranic Vocabulary

Rather than trying to learn conversational Arabic first, focus on the vocabulary that appears most frequently in the Quran. Research shows that understanding just 300-400 root words will give you comprehension of 70-80% of Quranic text. This approach provides immediate spiritual benefit and motivation.

5. Study the Three Core Sciences

Invest time in basic Nahw (grammar), Sarf (morphology), and Balaghah (rhetoric). These are the tools that unlock meaning. Even a foundational understanding of how Arabic grammar works will dramatically improve your comprehension when reading translations or listening to explanations.

6. Apply Knowledge Immediately

As you learn new vocabulary and grammar rules, apply them immediately to Surahs you already know. Take Surah Al-Fatiha and study it word-by-word, understanding the grammatical structure and morphological derivations. This immediate application reinforces learning and makes it spiritually meaningful.

7. Use the Research-Backed Advantage

Studies show that learners with “spiritual-integrative motivation” persist longer and achieve higher proficiency than those learning for purely academic or career reasons. Use your desire to understand the Quran as your primary motivator. When the grammar gets difficult, remind yourself why you started,to hear Allah’s words directly.

The most important step is to begin. Let your first step be your sincere intention, and let your next step be to seek structured knowledge through qualified teachers who can guide your journey systematically.

Conclusion

Learning Arabic is crucial for Muslims, deeply connecting faith’s spiritual, legal, historical, and cognitive dimensions. It enables direct access to the Quran and Sunnah, is foundational for Islamic law, and unifies the global Muslim community.

Reviving Arabic study in the modern era combats fragmentation, reinforcing religious integrity and civilizational renewal. It shifts believers from passive reception to active participation, allowing them to grasp Islam’s profound essence.

This journey transcends mere language, unlocking the faith’s core: transforming Quranic reading into intimate dialogue, superficial acts into deep connection, and reliance on others into confident personal understanding.

Despite the difficulty, the path begins with sincere intent and consistency. The ultimate aim is knowing the Creator through His chosen language.

May Allah grant ease and blessing. Alhamdulillah.

Recommended Learning Resources

For those ready to begin their Arabic learning journey, structured guidance from qualified teachers can dramatically accelerate progress and prevent common pitfalls. Consider exploring:

- Arabic Language Foundations: Comprehensive courses covering alphabet, pronunciation, grammar (Nahw), and morphology (Sarf)

- Quranic Arabic Specialization: Focused study on Quranic vocabulary and grammatical structures for direct Quran comprehension

- Tajweed and Recitation: Proper pronunciation rules essential for correct Quranic recitation

- Islamic Studies in Arabic: Advanced courses in Hadith, Fiqh, Tafsir, and Seerah for those with foundational Arabic knowledge

Platforms like NoorPath Academy offer structured pathways that combine these elements systematically, allowing you to build knowledge brick by brick with qualified instructors who understand both the linguistic and spiritual dimensions of Arabic learning.